Quadratic Form

The quadratic form of a matrix is a function of some vector. We’re going to discuss several cases, starting with the simplest case of a linear form.

Definitions

Linear form

The linear form of $\boldsymbol{x} = (x_1, \cdots, x_n)’$ is

$$ \begin{gathered} \boldsymbol{a}’\boldsymbol{x} = a_1 x_1 + a_2 x_2 + \cdots + a_n x_n \\ \boldsymbol{Ax} = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{\alpha}_1’\boldsymbol{x} \\ \vdots \\ \boldsymbol{\alpha}_m’\boldsymbol{x} \end{pmatrix} \end{gathered} $$

where $\boldsymbol{\alpha}_i’$ denotes the $i$-th row of $\boldsymbol{A}$. Each row of $\boldsymbol{Ax}$ is a linear combination of the elements of $\boldsymbol{x}$, which is why it is called a linear functional or linear form. Note that $\boldsymbol{A}$ is a given matrix, and $\boldsymbol{x}$ is just a vector with known dimensions1.

Bilinear form

Taking this a step further, we now have two vectors $\boldsymbol{x}$ and $\boldsymbol{y}$:

$$ \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ay}, \quad \boldsymbol{A}: m \times n, \boldsymbol{x}: m \times 1, \boldsymbol{y}: n \times 1 $$

We’re multiplying a row vector to a matrix, then two a column vector, so the outcome is going to be a scalar value. Again, only $\boldsymbol{A}$ is a known matrix, and the vectors $\boldsymbol{x}$ and $\boldsymbol{y}$ are just unknowns.

$$ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ay} &= (x_1, \cdots, x_m) \begin{pmatrix} a_{11} & \cdots & a_{1n} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ a_{m1} & \cdots & a_{mn} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} y_1 \\ \vdots \\ y_n \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \sum_{j=1}^n \sum_{i=1}^m a_{ij}x_i y_j \end{aligned} $$

For example, let

$$ \boldsymbol{A} = \begin{pmatrix} 2 & 1 & 3 \\ -1 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}, \quad \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ay} = 2x_1y_1 + x_1y_2 + 3x_1y_3 - x_2y_1 + x_2y_3 $$

For some fixed $\boldsymbol{x}$, it becomes a linear function of $\boldsymbol{y}$. Similarly if $\boldsymbol{y}$ is fixed, then it becomes a linear function of $\boldsymbol{x}$.

Quadratic form

The difference the bilinear form and the quadratic form is that now $\boldsymbol{x}$ and $\boldsymbol{y}$ are equal to each other, and thus $\boldsymbol{A}$ must be a square matrix.

Any $n \times n$ real matrix $\boldsymbol{A}$ determines a quadratic form in $n$ variables $\boldsymbol{x} = (x_1, \cdots, x_n)’$ by the formula

$$ \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} = \sum_{j=1}^n \sum_{i=1}^n a_{ij}x_i x_j = \sum_{i=1}^n a_{ii}x_i^2 + \sum_{i \neq j} a_{ij}x_i x_j $$

For example, let

$$ \boldsymbol{A} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 3 & 4 \end{pmatrix} $$

The quadratic form is then

$$ \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} = x_1^2 + 4x_2^2 + 2x_1x_2 + 3x_2x_1 = x_1^2 + 4x_2^2 + 5x_1x_2 $$

So why are we doing this? The point is that investigating properties of this function reveals properties about the matrix itself. Knowing the function $x_1^2 + 4x_2^2 + 5x_1x_2$ in the space $\mathbb{R}^2$ tells us a lot about $\boldsymbol{A}$.

Notes on the quadratic form

$\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{A}’\boldsymbol{x}$. The LHS $\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax}$ is a scalar and thus symmetric, so

$$ \left(\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax}\right)’ = \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{A}’\boldsymbol{x} = RHS $$

This implies that as far as quadratic forms are concerned, we can confine to symmetric matrices, i.e. for any $n \times n$ matrix $\boldsymbol{A}$, there exists a symmetric matrix $\boldsymbol{B}$ that has exactly the same quadratic forms.

$$ \boldsymbol{B} = \frac{\boldsymbol{A} + \boldsymbol{A}’}{2}, \quad \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Bx} = \frac{1}{2}\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} + \frac{1}{2} \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{A}’\boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} $$

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ and $\boldsymbol{B}$ are symmetric matrices, then

$$ \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Bx} \Longleftrightarrow \boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{B} $$

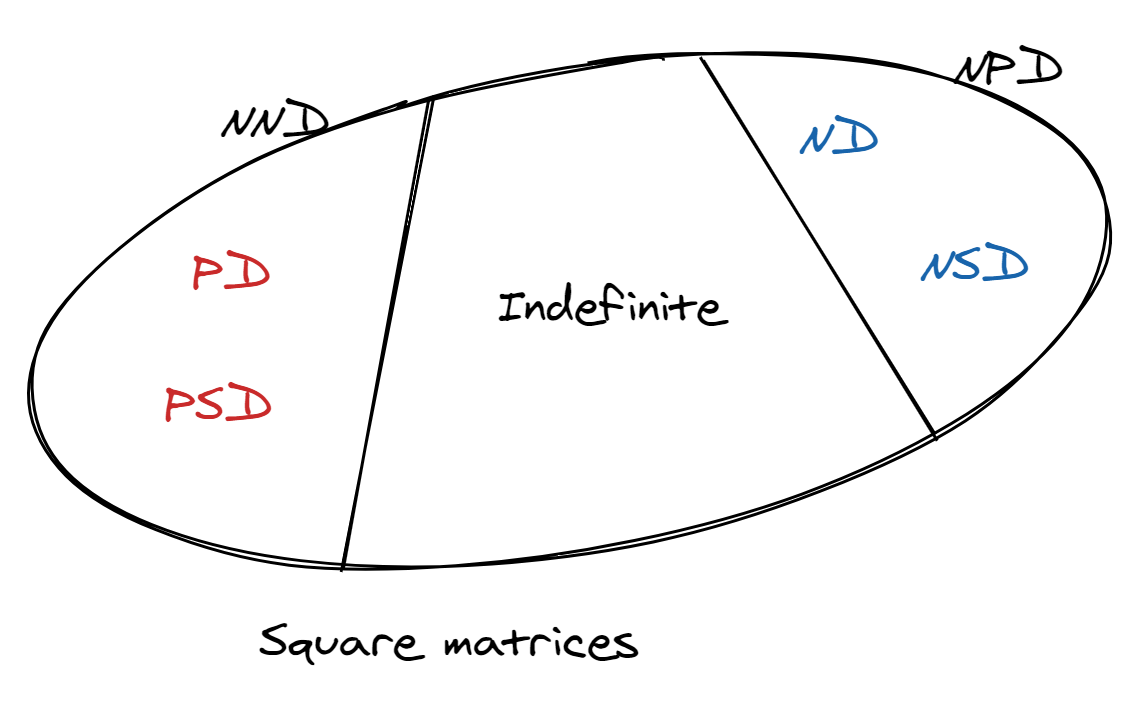

Categorizing quadratic forms

Now we’re ready to talk about categorizing matrices, or equivalently categorizing quadratic forms. The concepts we’re going to introduce come from a desire for notions about the signs of matrices. In elementary maths, we have $3 > 0$ and $-3 < 0$, but for two matrices:

$$ \boldsymbol{A} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 \\ 2 & 3 \end{pmatrix} \quad vs. \quad \boldsymbol{B} = \begin{pmatrix} 2 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 \end{pmatrix}, $$

we can’t easily say one is greater than the other. The notion of definiteness will help us with this comparison. Conceptually, we have

$$ \boldsymbol{A} - \boldsymbol{B} = \begin{pmatrix} -1 & 1 \\ 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix}, $$

and then we determine the definiteness of the matrix $\boldsymbol{A} - \boldsymbol{B}$ as a whole, and say “$\boldsymbol{A}$ is larger than $\boldsymbol{B}$” or the other way around.

Non-negative definite

The definition of non-negative definite (NND) matrices applies to quadratic forms as well as to matrices directly. A quadratic form $\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax}$ is NND (equivalently $\boldsymbol{A}$ is NND) if $\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} \geq 0$ for any $\boldsymbol{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$.

Clearly, $\boldsymbol{x} = 0$ yields $\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} = 0$. Two distinct cases for NND are:

- $\boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{0}$ is the only vector that yields zero. This case is called

positive definite(PD). - There are some $\boldsymbol{x} \neq \boldsymbol{0}$ that yield $\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} = 0$. This case is called

positive semi-definite(PSD).

Examples

The identity matrix is positive definite.

$$ \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ix} = x_1^2 + x_2^2 + \cdots + x_n^2 \geq 0 $$

The matrix of ones is positive semi-definite.

$$ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Jx} &= x_1^2 + \cdots + x_n^2 + 2(x_1 x_2 + \cdots + x_{n-1}x_n) \\ &= (x_1 + \cdots + x_n)^2 \geq 0 \quad \Rightarrow NND \end{aligned} $$

This can be zero if $x_1 + \cdots + x_n = 0$, so $\boldsymbol{J}$ is not positive-definite, and is thus positive semi-definite.

Non-positive definite

On the opposite side of NND matrices, we have non-positive definite (NPD) matrices. We say a quadratic form $\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax}$ is non-positive definite if $\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} \leq 0$. The two possible cases are:

Negative definite: $\boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{0}$ is the only vector to make $\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} = 0$.Negative semi-definite: similar to PSD but opposite.

Indefinite

Given a real number $x$, if we say $x$ is not non-negative, then $x$ is negative. However, things are different for matrices. If a matrix is not NND, we can’t safely say it’s NPD. There exists a big “gray area” in the middle for matrices that are neither NND nor NPD called indefinite matrices. For those, $\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax}$ can be negative and positive depending on $\boldsymbol{x}$.

Properties

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is NND/PD/PSD, then $-\boldsymbol{A}$ is NPD/ND/NSD, respectively.

If $\boldsymbol{D}$ is a diagonal matrix $\boldsymbol{D} = diag(d_1, \cdots, d_n)$, then

$$ d_i \geq 0 \, \forall i \Longleftrightarrow \boldsymbol{D} \text{ is NND} $$

This is because

$$ \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Dx} = d_1x_1^2 + d_2x_2^2 + \cdots + d_nx_n^2 \geq 0 $$

Following the same logic, we have

$$ d_i > 0 \, \forall i \Longleftrightarrow \boldsymbol{D} \text{ is PD} $$

Multiplying a positive scalar to $\boldsymbol{A}$ does not change the definiteness.

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ and $\boldsymbol{B}$ are both NND, then $\boldsymbol{A} + \boldsymbol{B}$ is NND2.

$$ \boldsymbol{x}’(\boldsymbol{A} + \boldsymbol{B})\boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} + \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Bx} \geq 0 $$

Similarly if $\boldsymbol{A}$ and $\boldsymbol{B}$ are both PD, then $\boldsymbol{A} + \boldsymbol{B}$ is PD.

However, if $\boldsymbol{A}$ and $\boldsymbol{B}$ are both PSD, $\boldsymbol{A} + \boldsymbol{B}$ is not necessarily PSD. $\boldsymbol{A} + \boldsymbol{B}$ is NND, but it could be PD or PSD.

Finally, if $\boldsymbol{A}$ is PSD and $\boldsymbol{B}$ is PD, then $\boldsymbol{A} + \boldsymbol{B}$ is PD.

A PD matrix is non-singular. An important corollary of this is that a PSD matrix is singular. This is one of the reasons why we put an emphasis on differentiating these two cases – singularity comes with a lot of properties!

To prove this, suppose $\boldsymbol{A}$ is singular. This means that the nullspace of $\boldsymbol{A}$ is not empty, i.e. there exists $\boldsymbol{x} \neq \boldsymbol{0}$ such that $\boldsymbol{x} \in \mathcal{N}(\boldsymbol{A})$. We then have

$$ \boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{0} \Rightarrow \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} = 0 $$

We have found a non-zero $\boldsymbol{x}$ that can make the quadratic form zero, which is contradictory to “$\boldsymbol{A}$ is PD”.

Suppose $\boldsymbol{A}: n \times n$ and $\boldsymbol{P}: n \times m$.

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is NND, then $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP}$ is NND. This can be easily proven using the quadratic form:

$$ \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{APx} = (\boldsymbol{Px})’\boldsymbol{A}(\boldsymbol{Px}) \Rightarrow \boldsymbol{y}’\boldsymbol{Ay} \geq 0 $$

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is PD and $r(\boldsymbol{P}) = m$, then $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP}$ is PD.

To show this, consider when $\boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{APx} = 0$. The fact that $\boldsymbol{A}$ is PD leads to $\boldsymbol{Px} = \boldsymbol{0}$. Since $r(\boldsymbol{P}) = m$, the $m \times m$ matrix $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{P}$ is non-singular, and $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{Px} = \boldsymbol{0}_m$ leads to $\boldsymbol{x} = \boldsymbol{0}$.

Similarly we can show that if $\boldsymbol{A}$ is PSD and $r(\boldsymbol{P}) = m$, then $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP}$ is PSD.

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is NND and $r(\boldsymbol{P}) < m$, then $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP}$ is PSD. From the properties of matrix rank we know that $r(\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP}) < m$, so it’s singular and can’t be PD.

Suppose $\boldsymbol{A}: n \times n$ and $\boldsymbol{P}: n \times n$ and non-singular.

- From (6) we know if $\boldsymbol{A}$ is PD, then $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP}$ is PD.

- If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is PSD, then $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP}$ is PSD.

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is PD, then $\boldsymbol{A}^{-1}$ is PD.

To prove this, it’s sufficient to show that $(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1})’$ is PD.

$$ (\boldsymbol{A}^{-1})’ = (\boldsymbol{A}^{-1})’\boldsymbol{A}\boldsymbol{A}^{-1} = \boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP} $$

where $\boldsymbol{P} = \boldsymbol{A}^{-1}$. From (7), we have $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP}$ is PD, so $(\boldsymbol{A}^{-1})’$ is PD.

Any principal submatrix of a PD (NND) matrix is PD (NND). A

principal submatrixstarts from the top-left corner of a square matrix, and is a square submatrix obtained by removing certain rows and columns.To show this, let

$$ \boldsymbol{P}_{n \times m} = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{I}_m \\ \boldsymbol{0}_{(n-m) \times m} \end{pmatrix} $$

and the rank of $\boldsymbol{P}$ is clearly $m$. $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP}$ is the $m \times m$ principal submatrix of $\boldsymbol{A}$:

$$ \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix}' \begin{pmatrix} 3 & 1 & 2 \\ 1 & 2 & 6 \\ 2 & 6 & 4 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \\ 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 3 & 1 \\ 1 & 2 \end{pmatrix} $$

Use (6) to see that $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{AP}$ is PD.

This can be used to prove certain matrices are not PD. For example,

$$ \boldsymbol{A} = \begin{pmatrix} -1 & 0 & 3 & 12 \\ 0 & -1 & 7 & 2 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \end{pmatrix} $$

cannot be a positive definite matrix because the top-left submatrix is $-\boldsymbol{I}_{2}$, which is negative definite.

Any diagonal elements of a PD (NND) matrix is positive (non-negative):

$$ \begin{gathered} \boldsymbol{A}: PD \Rightarrow a_{ii} > 0 \,\forall i \\ \boldsymbol{A}: NND \Rightarrow a_{ii} \geq 0 \,\forall i \end{gathered} $$

Note that this doesn’t go from right to left. To show this, let $\boldsymbol{p} = (0, \cdots, 0, 1, 0, \cdots, 0)’$ where only the $i$-th element is 1 and all the other $(n-1)$ elements are 0. $a_{ii} = \boldsymbol{p}’\boldsymbol{Ap}$ is positive definite, i.e. $a_{ii} > 0$.

Corollary of this, the trace of a PD matrix is positive, and the trace of an NND matrix is non-negative.

Let $\boldsymbol{P}: n \times m$ be any rectangular matrix. Then, $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{P}$ and $\boldsymbol{PP}’$ are both non-negative definite.

This is because for all $\boldsymbol{x}$, we have

$$ \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{Px} = (\boldsymbol{Px})’(\boldsymbol{Px}) = \|\boldsymbol{Px}\|^2 \geq 0 $$

Or we can use (6) and set $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{I}$.

If $r(\boldsymbol{P}) = m$, then $\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{P}$ is positive definite. If $r(\boldsymbol{P}) = n$, then $\boldsymbol{PP}’$ is positive definite.If $\boldsymbol{D}$ is diagonal and $\boldsymbol{P}$ is non-singular, then

$$ \boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{DP}: NND \Longleftrightarrow d_i \geq 0 $$

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is symmetric and idempotent, then $\boldsymbol{A}$ is NND.

$$ \boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{A}^2 = \boldsymbol{A}’\boldsymbol{A}: NND $$

The only positive definite symmetric idempotent matrix is $\boldsymbol{I}$. Any other projection matrix is positive semi-definite, i.e. singular.

Decomposition of symmetric matrices

Theorem 1

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is a symmetric matrix, then there exists a non-singular matrix $\boldsymbol{Q}$ such that $\boldsymbol{Q}’\boldsymbol{AQ}$ is diagonal.

For example,

$$ \boldsymbol{A} = \begin{pmatrix} 2 & 1 \\ 1 & 3 \end{pmatrix}, \quad \boldsymbol{Q} = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{pmatrix} $$

The $\boldsymbol{Q}$ matrix is not unique and there’s always a triangular $\boldsymbol{Q}$.

$$ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{Q}’\boldsymbol{AQ} &= \begin{pmatrix} a & 0 \\ b & d \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 2 & 1 \\ 1 & 3 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ 0 & d \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \begin{pmatrix} 2a^2 & 2ab + ad \\ 2ab + ad & \cdots \end{pmatrix} \end{aligned} $$

For this to be diagonal, we need $2ab+ad=0$, so

$$ \begin{cases} a=0 \\ d = -2b \end{cases} \quad \text{or} \quad \boldsymbol{Q}: \text{ singular} $$

We want the $\boldsymbol{Q}$ matrix to be singular, so the first case yields

$$ \boldsymbol{Q} = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ 0 & -2b \end{pmatrix} \xlongequal{e.g.} \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 1 \\ 0 & -2 \end{pmatrix} $$

We’re not proving this theorem here. An important corollary of this is if $\boldsymbol{A}$ is symmetric, then there exists a non-singular matrix $\boldsymbol{P}$ and a diagonal matrix $\boldsymbol{D}$ such that $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{DP}$. To show this, set $\boldsymbol{P} = \boldsymbol{Q}^{-1}$ and use the theorem:

$$ \begin{gathered} \boldsymbol{Q}’\boldsymbol{AQ} = \boldsymbol{D} \\ \boldsymbol{Q}’\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{DQ}^{-1} \\ \boldsymbol{A} = (\boldsymbol{Q}’)^{-1}\boldsymbol{DQ}^{-1} \\ \boldsymbol{A} = (\boldsymbol{Q}^{-1})’\boldsymbol{DQ}^{-1} \end{gathered} $$

Theorem 2

$\boldsymbol{A}$ is a symmetric non-negative definite matrix and $r(\boldsymbol{A}) = r$ $\Longleftrightarrow$ there exists $\boldsymbol{B}: r \times n$ and $r(\boldsymbol{B}) = r$ such that $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{B}’\boldsymbol{B}$.

To prove ($\Leftarrow$), see that $\boldsymbol{B}’\boldsymbol{B}$ is non-negative definite when $\boldsymbol{B}$ is rank $r$.

To see ($\Rightarrow$), by the corollary in Theorem 1 we have $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{PDP}’$ for some non-singular and diagonal $\boldsymbol{D}$. Since $\boldsymbol{PDP}’$ is non-negative definite, $d_i \geq 0$ for all $i$. Since $r(\boldsymbol{A}) = r$, exactly $r$ of the diagonals are positive, and $(n-r)$ of the diagonals are zeros. We can rearrange the $d_i$’s such that

$$ d_1 \geq d_2 \geq \cdots \geq d_r > d_{r+1} = \cdots = d_n = 0 $$

and we rearrange the columns of $\boldsymbol{P}$ accordingly. Then we take

$$ \boldsymbol{B}’_{n \times r} = [\text{first } r \text{ columns of } \boldsymbol{P}] \begin{pmatrix} \sqrt{d_1} & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & \sqrt{d_2} & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \cdots & \sqrt{d_r} \end{pmatrix} $$

from which we can see

$$ \boldsymbol{B} = \begin{pmatrix} \sqrt{d_1} & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & \sqrt{d_2} & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \cdots & \sqrt{d_r} \end{pmatrix}_{r \times r} \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{p}_1’ \\ \vdots \\ \boldsymbol{p}_r' \end{pmatrix}_{r \times n} $$

Now $\boldsymbol{B}’\boldsymbol{B}$ would be

$$ \begin{aligned} \boldsymbol{B}’\boldsymbol{B} &= [\boldsymbol{p}_1, \cdots, \boldsymbol{p}_r] \begin{pmatrix} \sqrt{d_1} & & \\ & \ddots & \\ & & \sqrt{d_r} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \sqrt{d_1} & & \\ & \ddots & \\ & & \sqrt{d_r} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{p}_1’ \\ \vdots \\ \boldsymbol{p}_r' \end{pmatrix} \\ &= [\boldsymbol{p}_1, \cdots, \boldsymbol{p}_n] \left[\begin{array}{ccc|c} d_1 & & & \\ & \ddots & & \huge0 \\ & & d_r & \\ \hline \\ & \huge0 & & \huge0 \end{array}\right] \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{p}_1’ \\ \vdots \\ \boldsymbol{p}_n' \end{pmatrix} \\ &= \boldsymbol{PDP}’ = \boldsymbol{A} \end{aligned} $$

This decomposition is important in that it’s related to the eigendecomposition that we’ll see later.

Corollary

$$ \boldsymbol{A}: \text{symmetric and NND} \Longleftrightarrow \exists \boldsymbol{B}: n \times n \text{ s.t. } \boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{B}’\boldsymbol{B} $$

Another version of this corollary is

$$ \boldsymbol{A}: \text{symmetric, NND, and } r(\boldsymbol{A}) = r \Longleftrightarrow \exists \boldsymbol{B}: m \times n (m \geq r) \text{ s.t. } \boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{B}’\boldsymbol{B} $$

Although there seems no restrictions on the rank of $\boldsymbol{B}$, see that if we have the left side, then we cannot hava $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{B}’\boldsymbol{B}$ where $\boldsymbol{B}$ is $m \times n$ and $m < r$. The rank of $\boldsymbol{B}$ must be $r$.

Properties

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is symmetric and NND, then

$$ \boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{0} \Longleftrightarrow \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} = 0 $$

Proving ($\Rightarrow$) is trivial. For the other direction, see that $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{P}$ for some $\boldsymbol{P}$.

$$ \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{x}’\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{Px} = \|\boldsymbol{Px}\|^2 = 0 $$

This means $\boldsymbol{Px} = \boldsymbol{0}$, thus $\boldsymbol{Ax} = \boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{Px} = \boldsymbol{0}$.

$\boldsymbol{A}$ is symmetric and positive definite $\Longleftrightarrow$ there exists a non-singular matrix $\boldsymbol{P}$ such that $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{P}$.

The inverse of a positive definite matrix $\boldsymbol{A}$ is positive definite:

$$ \boldsymbol{A}^{-1} = \boldsymbol{P}^{-1}(\boldsymbol{P}’)^{-1} = \boldsymbol{P}^{-1}(\boldsymbol{P}^{-1})' $$

What if $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{DP}$ is a positive semi-definite matrix? Similarly $\boldsymbol{P}$ is non-singular and $d_i \geq 0$ with exactly $r$ elements being positive and the others being zero. We want to find the generalized inverse of $\boldsymbol{A}$.

We rearrange the diagonals of $\boldsymbol{D}$ such that

$$ \boldsymbol{D} = diag(d_1, \cdots, d_r, 0, \cdots, 0) $$

One way to find a generalized inverse is to define

$$ \begin{gathered} \boldsymbol{D}^* = diag\left(\frac{1}{d_1}, \cdots, \frac{1}{d_r}, 0, \cdots, 0 \right) \\ \boldsymbol{G} \triangleq \boldsymbol{P}^{-1}\boldsymbol{D}^* (\boldsymbol{P}’)^{-1} \end{gathered} $$

Then we have

$$ \boldsymbol{AGA} = \boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{DPP}^{-1}\boldsymbol{D}^* (\boldsymbol{P}’)^{-1}\boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{DP} = \boldsymbol{P}’\boldsymbol{DP} = \boldsymbol{A} $$

So $\boldsymbol{G}$ is also NND. Note that this means we can always find a positive semi-definite generalized inverse for $\boldsymbol{A}$. This doesn’t mean all $\boldsymbol{G}$’s are PSD!

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is symmetric and non-negative definite, and $tr(\boldsymbol{A}) = 0$, then $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{0}$.

From the fact that $\boldsymbol{A}$ is NND, we can rewrite it as $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{BB}’$ for some $\boldsymbol{B}$. We then have

$$ tr(\boldsymbol{BB}’) = \sum_{i, j} b_{ij}^2 = 0 \Rightarrow \boldsymbol{B} = \boldsymbol{0} \Rightarrow \boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{0} $$

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is positive definite and $\boldsymbol{B}$ is non-negative definite and symmetric3, $tr(\boldsymbol{AB}) > 0$.

If the rank of $\boldsymbol{B}$ is $r$, we can rewrite $\boldsymbol{B} = \boldsymbol{Q}’\boldsymbol{Q}$ where $\boldsymbol{Q}$ is $r \times n$. Then,

$$ tr(\boldsymbol{AB}) = tr(\boldsymbol{AQ}’\boldsymbol{Q}) = tr(\boldsymbol{QAQ}’) $$

$\boldsymbol{QAQ}’$ is a positive definite matrix, and its trace is strictly positive.

$\boldsymbol{A}$ is an $n \times n$ symmetric non-negative definite matrix4, and we partition it into

$$ \boldsymbol{A} = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{T}_{r \times r} & \boldsymbol{U}_{r \times s} \\ \boldsymbol{V}_{s \times r} & \boldsymbol{W}_{s \times s} \end{pmatrix} $$

where $\boldsymbol{T}$ and $\boldsymbol{W}$ are square. Then,

$$ \begin{gathered} \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{U}) \subset \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{T}), \quad \mathcal{R}(\boldsymbol{V}) \subset \mathcal{R}(\boldsymbol{T}) \\ \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{V}) \subset \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{W}), \quad \mathcal{R}(\boldsymbol{U}) \subset \mathcal{R}(\boldsymbol{W}) \end{gathered} $$

To prove these, again we can rewrite $\boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{B}’\boldsymbol{B}$ where $\boldsymbol{B}: n \times n$. Consider the partition $\boldsymbol{B} = [\boldsymbol{E}_{n \times r} \quad \boldsymbol{F}_{n \times s}]$. Matrix $\boldsymbol{A}$ is

$$ \boldsymbol{A} = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{E}’ \\ \boldsymbol{F}' \end{pmatrix} [\boldsymbol{E} \quad \boldsymbol{F}] = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{E}’\boldsymbol{E} & \boldsymbol{E}’\boldsymbol{F} \\ \boldsymbol{F}’\boldsymbol{E} & \boldsymbol{F}’\boldsymbol{F} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \boldsymbol{T} & \boldsymbol{U} \\ \boldsymbol{V} & \boldsymbol{W} \end{pmatrix} $$

This is pretty much the end of the proof. For example, $\mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{U}) = \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{E}’\boldsymbol{F}) \subset \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{E}’)$, and $\mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{T}) = \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{E}’\boldsymbol{E}) = \mathcal{C}(\boldsymbol{E}’)$.

Some properties about the determinant:

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is positive definite, then $|\boldsymbol{A}| > 0$.

One way to prove this is to write $\boldsymbol{A}$ as $\boldsymbol{BB}’$ where $\boldsymbol{B}$ is non=singular. $|\boldsymbol{A}| = |\boldsymbol{B}||\boldsymbol{B}’| = |\boldsymbol{B}|^2 > 0$.

If $\boldsymbol{A}$ is positive semi-definite, then $|\boldsymbol{A}| = 0$.

Just like when we first learned about solving $x-1=0$, where $x$ denotes some unknown number. ↩︎

These conclusions cannot be generalized to $\boldsymbol{A} - \boldsymbol{B}$ or $\boldsymbol{AB}$. ↩︎

$\boldsymbol{AB}$ is not necessarily non-negative definite. ↩︎

In the statistical context, $\boldsymbol{A}$ is a variance-covariance matrix, $\boldsymbol{T}$ is the covariance matrix of part of the variables, $\boldsymbol{W}$ is the covariance matrix of the other part of the variables, and $\boldsymbol{U}$ and $\boldsymbol{V}$ are the cross-covariance matrices. ↩︎

| Oct 23 | Projection Matrix | 4 min read |

| Oct 07 | Matrix Trace | 4 min read |

| Nov 18 | Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors | 20 min read |

| Oct 26 | Determinant | 6 min read |

| Oct 21 | Generalized Inverse | 4 min read |

Yi's Knowledge Base

Yi's Knowledge Base